Preparing for the apocalypse with the mother of American modernism.

ALEXANDRA MARVAR

Georgia O’Keeffe’s fallout shelter is a subterranean chamber of white cinder blocks, comparable in size and charm to the interior of a cargo van. The door is tucked into a bluff facing the edge of the artist’s four-acre property in the painted deserts of northern New Mexico.

As my own apocalyptic anxiety continues to tick upward, I find some grounding comfort in its existence: this world-famous painter of petals and bones, in her Ferragamo flats and wrap dress, who wasn’t known at all for being apocalyptic, spent the early 1960s casually and quietly fortifying her home for the end of the world. We love art that is beautiful, but we crave art that is relatable; in O’Keeffe’s renderings of natural objects and undulating pastel landscapes, viewers see timelessness, sensuality, and the eerie power of the natural world. Inside O’Keeffe’s spartan bunker, I see myself.

But, there is virtually nothing online about what she built available for my reading. None of her thoughts, motives, or plans—just brief, scant mentions in decades of literature, and one black-and-white thumbnail of a nondescript door in the dirt. So, I decided to make the pilgrimage some 60 miles north of Santa Fe to the village of Abiquiú to see it for myself.

“While her reputation for being poised, self-possessed, and unafraid dominated her art-world narrative, she was open about her anxiety.”

O’Keeffe was born in 1887 into a fraught postbellum America. A teacher at the beginning of World War I, she would tell her biographers in her later years about how traumatized she was to think of her students being sent away to fight. She lived through the Depression, World War II, the Vietnam War, and much of the Cold War. Perhaps this is why the artist was a bundle of nerves.

“People think I’m very quiet ... but I’m very busy inside,” O’Keeffe says in a video that plays on loop in her eponymous museum in Santa Fe. Following intense career stress and the airing of her husband Alfred Stieglitz’s extramarital affair, she suffered two nervous breakdowns at the peak of her career in New York. While her reputation for being poised, self-possessed, and unafraid dominated her art-world narrative, she was open about her anxiety: innumerable self-help books lean on her popular quote, “I’ve always been absolutely terrified every single moment of my life, and I’ve never let it stop me from doing a single thing I wanted to do.”

O’Keeffe’s life, and her unprecedented success as a female artist, relied deeply on this ability to counter her fears. She never felt freer, healthier, or more productive than she did with a place of her own in New Mexico, and began spending summers in a cottage at Ghost Ranch—21,000 acres of desert just north of Los Alamos. Ten years later, in December 1945, she bought a house down the road in Abiquiú-an adobe ruin with coveted irrigation rights that would permit her a vast fruit and vegetable garden.

“O’Keeffe’s life, and her unprecedented success as a female artist, relied deeply on this ability to counter her fears.”

Over the next few years, a crew of friends and workers rebuilt most of the centuries-old original structure from the ground up while O’Keeffe settled the late Stieglitz’s estate in New York and prepared to move to Abiquiú full-time. She arrived for good in 1949—the year the Soviet Union detonated their first successful nuclear test in the tundra of Kazakhstan. The Cold War was in full swing.

Throughout the 1950s, nuclear tests exploded over the New Mexican desert, echoing the Manhattan Project’s first test—codenamed “Trinity”—which detonated in remote central New Mexico at nearly 6 o’clock one July morning in 1945. It lit up the sky like a false dawn, fractured adobe walls, and rattled windows hundreds of miles from the blast site. O’Keeffe would have seen and felt Trinity from Ghost Ranch that summer. When she began to make her home in Abiquiú, she knew well that the nerve center of American nuclear innovation, Los Alamos Laboratory, was hardly 30 miles away.

For O’Keeffe, the reality of Los Alamos may have felt even more present: years after moving to Abiquiú full time, she continued to paint at nearby Ghost Ranch in the summers, where some of the other guests signed in under pseudonyms and huddled in the common spaces, talking theoretical physics, and looking quite out of place. Among them was Robert Oppenheimer, the father of the atomic bomb, who spearheaded the Manhattan Project and who named Trinity after the poetry of John Donne.

“This world-famous painter of petals and bones spent the early 1960s casually and quietly fortifying her home for the end of the world.”

O’Keeffe would go on to host the likes of Joni Mitchell, Allen Ginsberg, and Ralph Lauren at Abiquiú. But the visitor who most piqued the curiosity of her assistants was the unnamed Los Alamos scientist who would visit for hours, describe his research, and invite her on exclusive tours of the particle accelerator.

Today’s threats are more plentiful, and more abstract, than they were at the dawn of the nuclear age: doomsday bunker sales spiked before Y2K, after Fukushima, and again following Donald Trump’s election. Luxury bunker suppliers claim a 700 percent sales increase since 2015. Reports of the world’s wealthiest prepping in far-flung locales for some unknown catastrophe grow more common. But a bunker is no match for rising sea levels, global food shortages, an unstoppable viral outbreak, or a Blade Runner data blackout. How can we ever be fully prepared?

At least in the 1960s, people felt they knew what they needed to do: nuclear fallout shelters gave Americans an ostensibly tangible way to engage in their safety—a sense of control. President Kennedy declared shelters a civic responsibility. Instructional pamphlets were distributed widely.

“Let us take a hard look at the facts,” writes the Office of Civil and Defense Mobilization in The Family Fallout Shelter, published in 1959. “In an atomic war, blast, heat, and initial radiation could kill millions ... Any mass of material between you and the fallout will cut down the amount of radiation that reaches you. Sufficient mass will make you safe.” This unexpected note of hope is accompanied by actionable blueprints.

By 1965, an estimated 200,000 shelters had been built across the country. Some argued this federal push only fueled America’s wartime anxiety, while others found solace in “sufficient mass.” For those with the motivation and means, it must have been therapeutic to have a concrete survival plan. O’Keeffe’s was as solid as they came.

“By 1965, an estimated 200,000 shelters had been built across the country.”

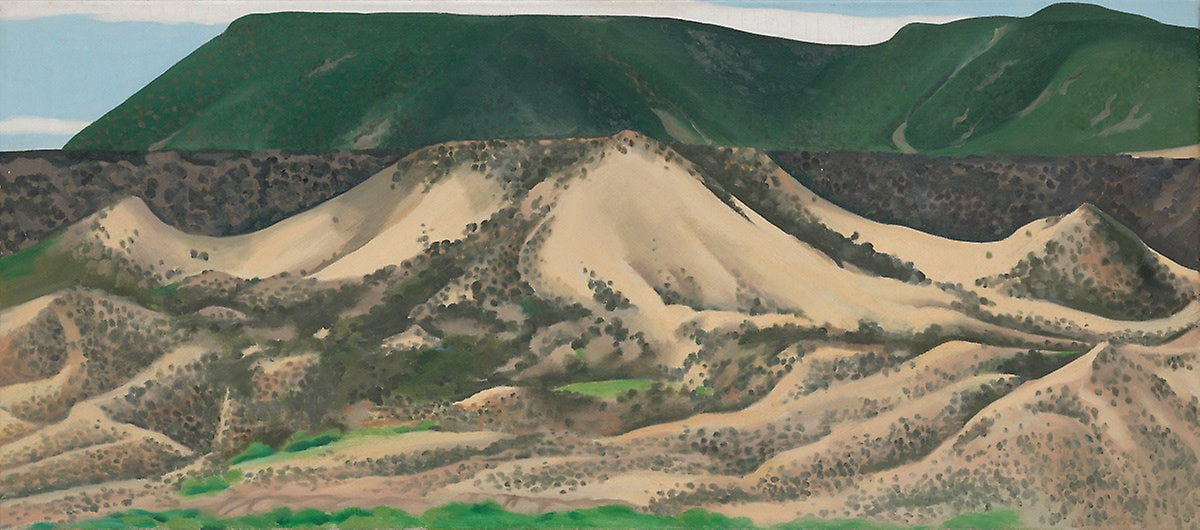

The Georgia O’Keeffe Welcome Center is a brand new adobe box that looks like it dropped out of the sky onto an otherwise wild two-lane highway. Guests board a shuttle to the artist’s sprawling single-story adobe palazzo with its sweeping views of the Chama River Basin.

On the tour, photography is forbidden, and we are instructed to touch nothing. After weaving in and out of a maze of rooms and courtyards, we make our way into the inner sanctum: the studio. Through big picture windows, I take in the panorama that inspired O’Keeffe’s mid-century canvases of cottonwood foliage. I never cared much for those paintings. Instead, I’m transfixed by the two bold pops of color beyond the more manicured part of the yard: short, bright orange ventilation pipes protruding from the underground. Entering the fallout shelter is an optional addendum to the 90-minute tour. Most guests demur, but I follow our guide out of the studio toward the pipes, around the bluff, and through the door.

A horseshoe on a ledge above the entrance is heels up for good luck. At the bottom of a 10-foot staircase is a high shelf with a pair of silver containers labeled WHEAT and a Christmas tin, contents unknown. Radiation travels in a straight line, so this entrance zigzags. A right down the steps and then a sharp left through the interior door—two thick panels of wood separated by a quarter-inch layer of lead—and I find myself in a box in the gut of the hillside.

“ It must have made her feel powerful, but the prospect of being a woman in one’s 70s and surviving the apocalypse alone feels maybe more terrifying to me than perishing in it.”

Two sets of metal bunks are affixed to a wall. Old newspapers the artist kept from the Cuban Missile Crisis are laid out to set the scene. The “meals ready-to-eat” are long gone, but a tall water tank looms in the corner and shelves are populated with their original contents: a sunshine yellow Geiger counter the size of a shoebox, a couple dozen cans of Sterno, a portable toilet (plus refills), a sharpened pencil, a rotary phone with a frayed cord, a box of Kotex.

On the far wall is a silver oval: the Whittaker Power Vent, a hand-cranked air filter connected to the orange pipes above. I’m thrilled to see it—according to David Monteyne, author of Fallout Shelter: Designing for Civil Defense in the Cold War, it’s one of the key distinctions between a futile bomb shelter or a retrofitted wine cellar and world-class apocalypse-proofing. It must have made her feel powerful, but the prospect of being a woman in one’s 70s and surviving the apocalypse alone feels maybe more terrifying to me than perishing in it.

After my visit, I ask Pita Lopez, an assistant to O’Keeffe for years beginning in the 1970s and who still works with the museum today, if O’Keeffe ever talked about why she built her underground room. “We understand she built it because she wanted to be around to see what the landscape would look like if there ever was a catastrophe,” Lopez responds. O’Keeffe’s version of “keep calm and carry on,” she explained, was a function of morbid curiosity. It seems she wasn’t obsessed with surviving the apocalypse after all; she just wanted to paint the aftermath.