The artist on interpreting joy, childhood discrimination, and smoking with a cochlear implant.

AS TOLD TO PATTY CARNEVALE

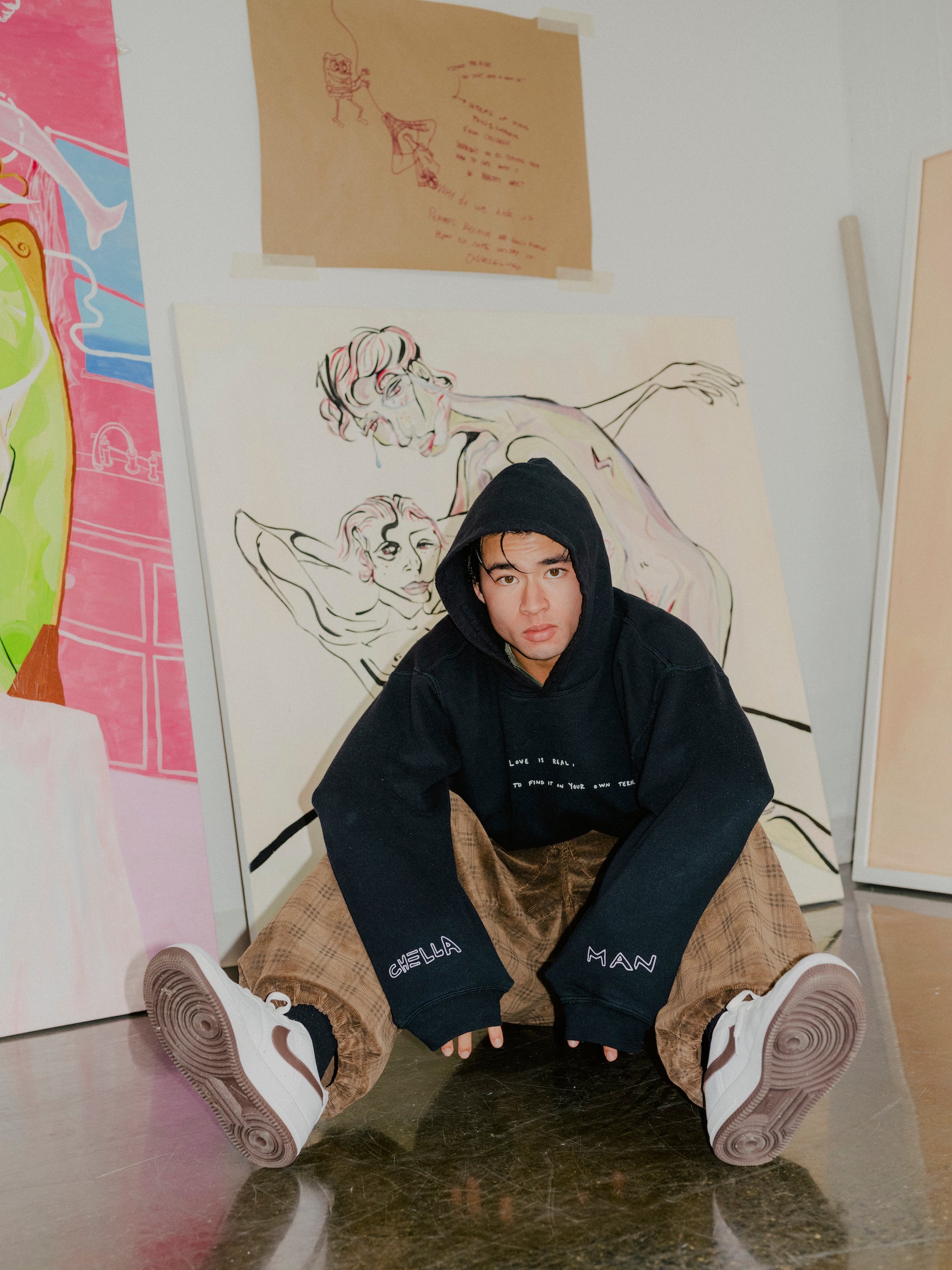

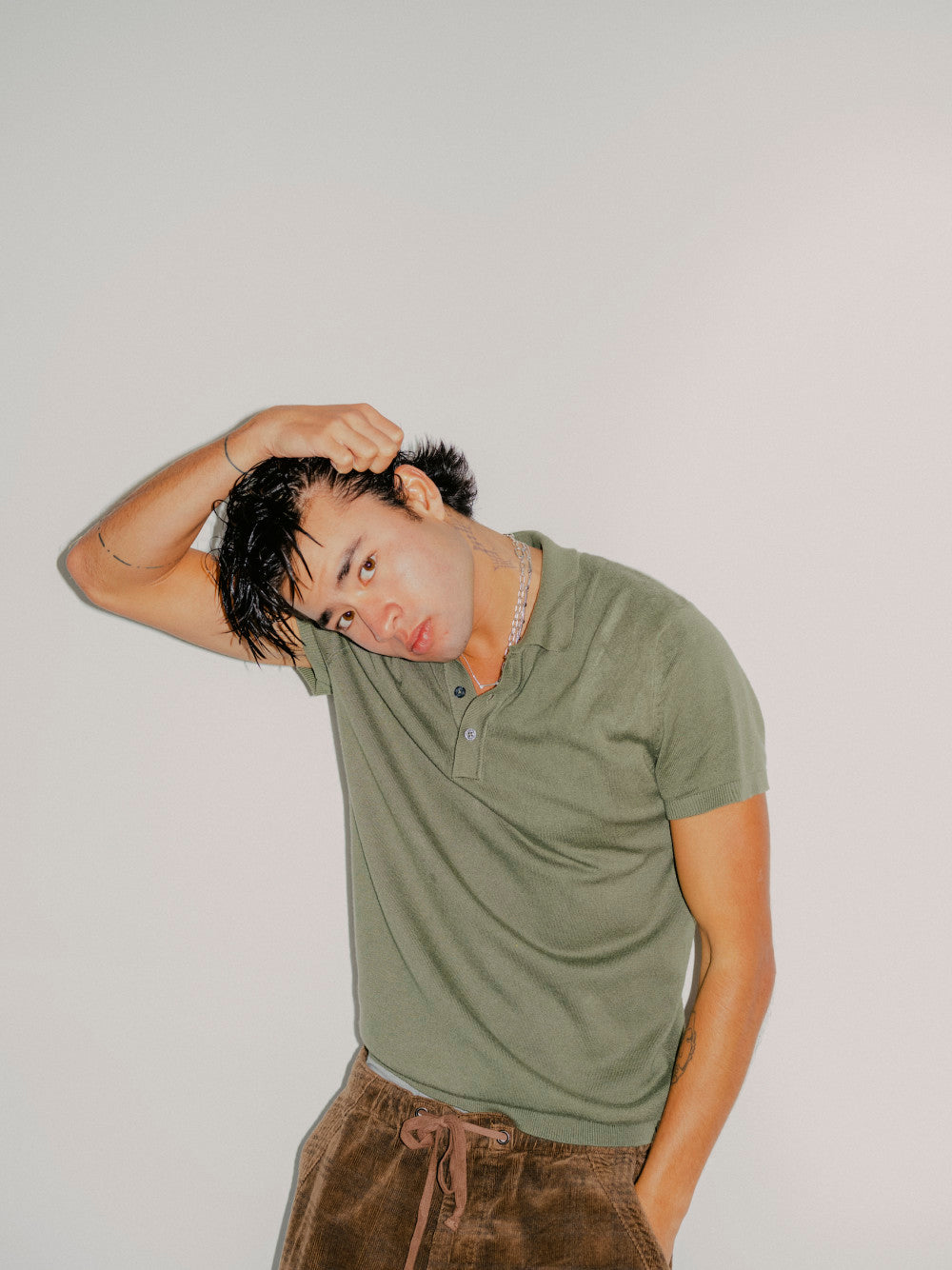

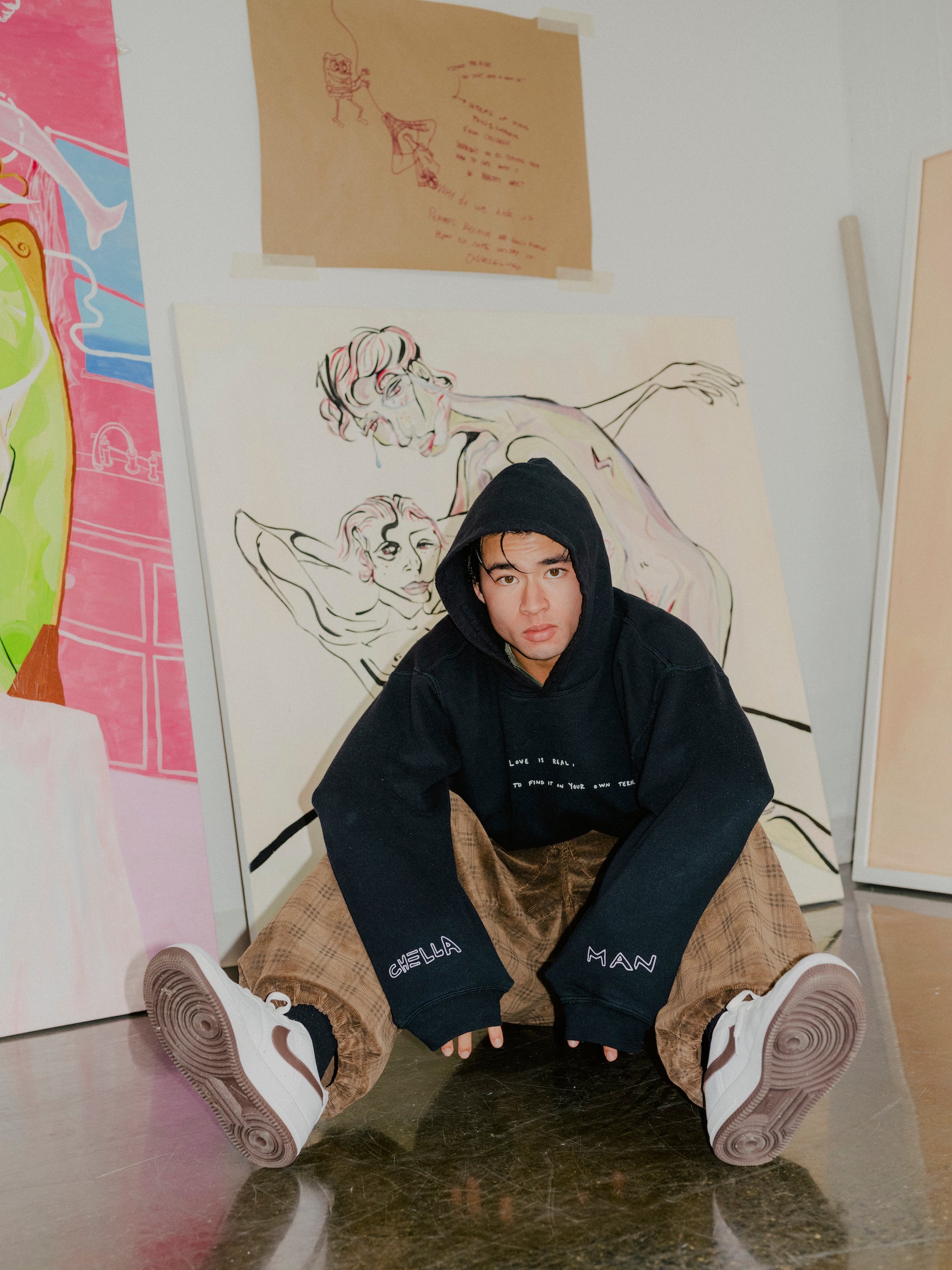

How I identify is constantly changing. At this very moment, I identify first and foremost as an artist. In Western society, people say their name, their age, and now pronouns and ethnicity and sexuality and stuff. So that’s usually how I introduce myself. Like, “Hi, my name is Chella Man, I’m 23 years old. I’m transmasculine, gender queer, Jewish, Chinese, deaf, and an artist.” In my ideal world, I’d just be like, “Hi, I’m Chella,” and then figure out how to be with people from there.

I was born in a very conservative small town in central Pennsylvania. There was no representation around me. There was no queer culture, there was no deaf guidance, and it was a predominantly white town. I struggled a lot with understanding who I was and what possibilities were open to me. I come from a very academic family, so I worked really hard in school and was able to graduate early, thank goodness. I could not spend another year in central Pennsylvania.

How I identify is constantly changing. At this very moment, I identify first and foremost as an artist.